The incredible speed of progress in AI-assisted application development is currently unleashing a wave of permissionless, creative innovation similar to the early days of the web, something I like to call the ‘save as html…’ era.

The mid-to-late 1990s were a time of creative and permissionless innovation, the beginning of the world wide web. In that age of static, simply-hosted websites, the lack of tooling, platforms, and established frameworks created constraints that forced a type of scrappy and even weird style of web development for anyone bold, nerdy, or quirky enough to have something unique to say and wanting to get it out there as quickly as possible. In those days, if you wanted to create content around one of your personal interests, you weren’t posting on X, LinkedIn, Facebook, or Medium (all centralized ‘web 2.0’ platforms that did not yet exist). You likely also weren’t pulling down the latest javascript framework, coding custom components, and tinkering with a continuous integration and deployment pipeline. Those developer norms also did not yet exist!

Rather than post to a centralized content platform or engage in a feat of software engineering, creative and expressive individuals would often create documents in MS Word, save as html, and upload to one of the many ad-supported free web hosting platforms of the era (such as GeoCities, Angelfire, or Tripod). The more technically-inclined tinkerers might have added some <blink> tags, spiced up their pages with some animated gifs and hit counter widgets, or written some primitive javascript to do something like make the background change color, have text bounce around the page, or play a song. Of course, the code generated by Word and other WYSIWYG creation tools of the day was absolutely terrible, and the resulting web pages were filled with bugs. But none of that mattered! This sort of scrappy, low-fidelity burst of permissionless creativity sparked an excitement that pulled millions of people online. It expanded peoples’ imagination for what the internet could make possible and the expansive role it would undoubtedly play in our society.

Since then, ‘web development’ became professionalized as a field of software engineering, and centralized platforms emerged and grew into some of the largest and most valuable companies on earth. There are well-paved paths for how to build applications on the internet, and the technical infrastructure now exists to create services that scale to millions or even billions of users. While these represent transformative innovations that largely improve our quality of life, some of the spirit of scrappy innovation has been lost.

Generative AI, however, is creating a new inflection point for the growth of creativity online. Over the past year or so, there has emerged a plethora of tools that streamline the speed and ease of creation for developers and even allow non-coders to build some pretty compelling applications. Tools such as v0, bolt.new, and replit have some pretty impressive capabilities out of the box, and the pace of adoption for the Cursor IDE is unprecedented. Even as an experienced developer, the ability to easily and quickly work with libraries, languages, and systems with which you have no prior familiarity is pretty amazing, and it expands the scope of what you can achieve while lowering the activation energy of getting started. For example, while I’m an experienced programmer when it comes to automation, analytics, and data, my front-end skills are lacking, and I have zero experience with voice or telephony. Using Cursor, I recently built an interactive, visually pleasing math app for my 8 year old and created a voice-based AI agent for personal use, complete with Twilio and Google Drive integrations. AI coding tools are still early, and I can’t imagine building those apps without knowing how to code and understanding/editing what the AI is writing, but it’s easy to paint a picture of how such technologies will improve.

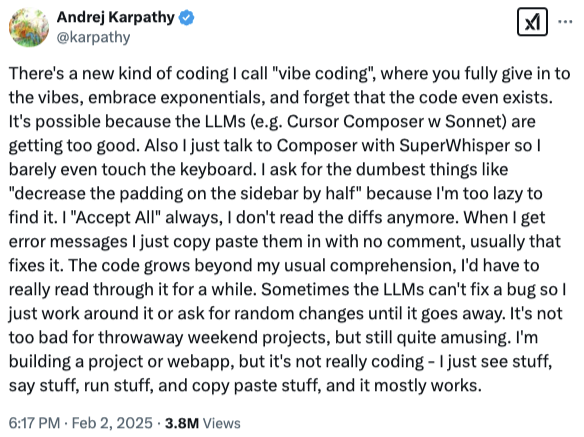

For the truly intrepid, it’s becoming possible to build largely by writing prompts, accepting changes, and correcting bugs as you go, rather than coding by hand. Prominent AI engineer Andrej Karpathy calls this “vibe coding”. This practice feels very, very weird, even dirty. But it sure is fun, and as models improve, it’s going to keep getting better. Perhaps more importantly, it’s going to lower the cost of experimentation and create opportunities to build amazing things for people who never would have considered themselves developers.

In the next year or 2, we’re going to see a TON of really bad code and buggy apps. I believe this is good! No, you shouldn’t build financial infrastructure or medical device software with this sort of technique (yet*). BUT the inevitable explosion of weird and divergent experiences will catalyze an entirely new wave of innovation in the world of technology and open peoples’ minds to a far more expansive vision of the possible future.

I’m excited by the ability of generative AI to facilitate self-expression and creativity, whether through code, art, or writing. As these technologies continue their rapid advance, they have the ability to open the door to a greater breadth of innovation from a broader set of individuals. Indeed, we can recapture the magic of the early web while also benefiting from the maturity and scale of the modern internet.

*people used to say this about the web generally, but eventually a new system may become hardened enough to not just be acceptable for these kinds of use cases but even superior